- Home

-

Private banking

-

LGT career

On the title cards of artworks in major museums and galleries, you'll often see the words "gift of", recognizing the individuals whose donations enable everyone to experience the best of the world's art and culture.

Room 12 of Barcelona's Museu Picasso holds a portrait that grabs the attention and confounds the eye. It depicts a man in the ruff collar and feather-trimmed hat favoured by sixteenth-century Spanish nobles.

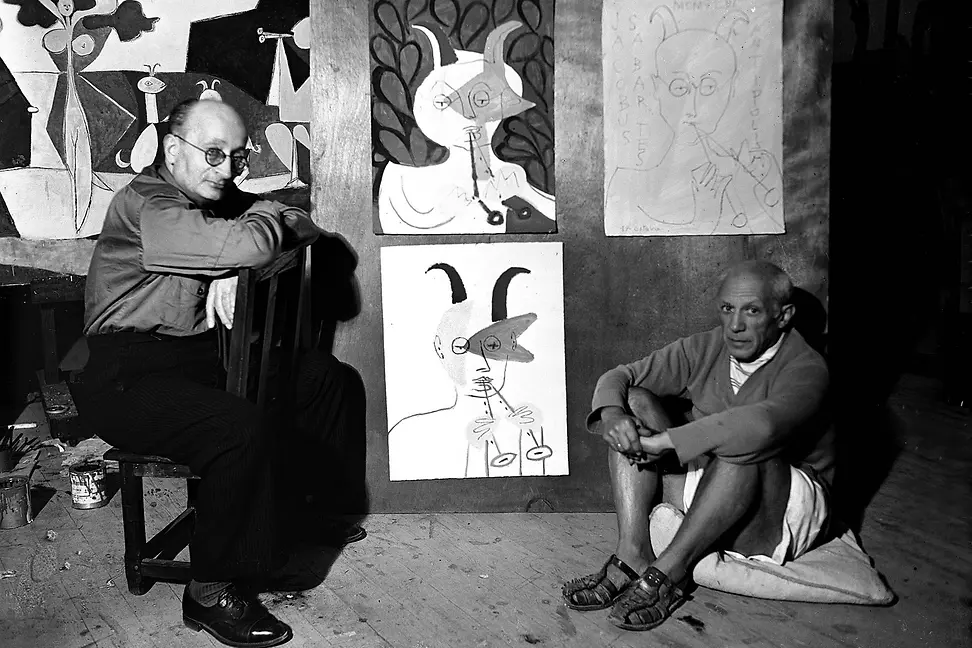

But this is no Renaissance-era artwork. Painted in 1939, the portrait pulls the face apart, showing the nose in profile, the lips in a frontal view, and bespectacled eyes veering off to the left. The effect is disturbing, yet it brilliantly conveys the complexity of a human being, showing the different sides of the man in a single image.

This is Picasso in a highly experimental mood, tearing up the artistic rulebook as he did in paintings like "Guernica" and the portraits of Dora Maar, also created in the 1930s. But the painting's significance goes further: the man in the portrait is Jaume Sabartés, and without him, this museum would not exist.

That's because in 1962, Sabartés, Picasso's secretary and biographer, donated his personal collection of the Spanish artist's works to the city of Barcelona on condition that they formed the basis for a museum dedicated to the artist.

By contrast, for another artist and collector, it was having her donation declined that led her to create a gallery that would become a major museum dedicated to American artists. Wealthy patron of the arts and sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney originally offered the more than 500 works in her collection to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. When the Met turned them down, she adapted three houses in Greenwich Village to exhibit the art - and the Whitney Museum of American Art was born.

In making these gifts, Sabartés and Whitney were following in a tradition that has enriched many of the world's great art museums. Think of, for example, Madrid's Thyssen museum, created in the former Palacio de Villahermosa for the collection of Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Artists also donate their own works to museums. The gifts of Wu Guanzhong and his family over the years to the Hong Kong Museum of Art (HKMA) have enabled the museum to build up a significant body of his work.

A twentieth century master painter, Wu Guanzhong created artworks that combine Western and Eastern influences, such as the Western style of Fauvism and the Eastern style of Chinese calligraphy. HKMA now has the world's largest collection of his art.

Some are bequests, enabling the donor to keep the artwork in their home while they are alive, knowing that on their death, it will be transferred to a museum.

At the Kunsthistorisches Museum - whose Habsburgs' collection was placed under the protection of the young Republic of German-Austria after the fall of the monarchy in 1918 - several donors have made such commitments in honour of the approaching retirement of Sabine Haag after 16 years as director general.

For the Princely House of Liechtenstein, Austria is home to many of the artworks that make up the family's Princely Collections. In the Garden Palace and the City Palace, both in Vienna, members of the public can see works from a collection that, thanks to an ongoing acquisitions policy, is now made up of more than 30,000 objects. Built up since the 16th century and featuring major works from five centuries of European art, this is one of the world's largest private art collections

One option for directors and curators, says Haag, is to approach an individual with a request to loan an artwork to the institution. Seeing their work hanging on the wall of a world-class gallery like the Kunsthistorisches Museum can make an impression. "Sometimes this is the first step towards a donation," she says.

When one long-term loan became a gift, it made headlines. In November 2024, London's British Museum received its biggest ever donation, when the Sir Percival David Foundation made a permanent gift of its collection of about 1700 Chinese ceramics. Valued at 1.3 billion USD, it is the most valuable donation of art in UK museum history.

Whether a short-term loan, a permanent loan, or an outright gift, before an artwork ends up at a museum or in an exhibition, a complex set of decisions needs to be made by both donor and recipient. The first step is for the donor to ask themselves the right questions. One of the most important is what the donor wants to achieve with their gift, says Jean Paul Warmoes, chief executive officer of Myriad USA, the US arm of the Brussels-based King Baudouin Foundation.

Myriad USA, whose philanthropic services include helping people who want to make donations of artworks or collections overseas, recently helped Sir Simon Schama, the historian, writer, art critic, and television presenter, and his partner, leading geneticist Dr Virginia Papaioannou, to make a gift to the Rijksmuseum of a small Rembrandt etching copperplate that the couple had owned since the 1990s. While part of their motivation was to enable the plate to be seen by the wider public, they also strongly believed that the work should be returned "home" to the country where it was created.

However, not everyone has a Rembrandt, and major museums are unlikely to accept works of lesser significance unless they fill a specific gap in their collection, or add to the museum's understanding of the artist, the work, or the historical period. For example, the Kunsthistorisches Museum has 12 works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. "If a thirteenth was offered to us as a donation, we would check that it would add to our research knowledge," says Haag.

Even when a leading institution does accept a donor's artwork, it might not always be on display. "If you're going to give it to one of the leading international museums, there might be a risk that it spends more time in storage," says Warmoes. On the other hand, in a smaller museum, the work might become part of the permanent collection. "Let's not forget that regional museums have an educational purpose," Warmoes adds. "And they serve the local community, which is proud of its heritage and culture."

Donors should also be aware that museums exercise extreme caution before accepting a work. Extensive legal and artistic due diligence is conducted on every potential gift to confirm its provenance and ensure it fits with the institution's historical and artistic goals - something Haag calls "the storyline of your collection" - and meets formal accessioning policies.

"People may think a museum is bound to want their artwork," says Amanda Gray, a partner at British law firm Mishcon de Reya and a specialist in art law. "But they have to make very careful decisions about what they acquire."

A museum, she explains, will consider whether the artwork fits into the artistic or historical focus of its collection and the cultural mood of the moment. "Over the past few years there's been a lot of reflection about the kinds of artworks to include in exhibitions and collections, and whether they are inclusive enough," she says.

Moreover, museums have to be extremely careful about the origin of artworks and whether the donor has what's known as "good title" (ie they are the legal owner of the work) and can transfer that by deed of gift.

Red flags are prompted by artefacts including ivory, culturally significant or sacred objects, and anything that might have been looted, whether from an ancient temple or by the Nazis. Museums also need to consider whether or not they want to be associated with the individual making the donation, depending on how they acquired their wealth.

Even if a potential gift passes these tests, a museum must also consider what funding is required for its conservation, insurance, and storage, particularly for large works or sculptures.

Donations of artworks can also help to offset taxes. In the Netherlands, for instance, artworks with national cultural or art-historical significance can be transferred to the Dutch state as a means of paying inheritance tax.

However, tax deductions are far from the only motive for giving artworks. When he established the Buddhist Art Museum at the Tsz Shan Monastery in Tai Po, Hong Kong, Li Ka-shing wanted to create both a museum and a spiritual centre. The museum is based on artworks that the Hong Kong billionaire donated, or were purchased by the foundation he created in 1980. As the museum's mission statement explains, it hopes to "promulgate Buddhist teachings" by helping visitors, through the appreciation of Buddhist art, to lead "a purified, purposeful life".

Another benefit of making a gift of an artwork is that once in a museum, donors know it will be well looked after, and the public can gain pleasure from something that was once in a private collection. "There's a generosity to this," says Warmoes. "I don't think people wake up thinking about the tax deduction."

Nor does every donor want recognition for the gift. "For some people it's very important to create an artistic or collector's legacy, but for others, they want to be anonymous and just have it noted as being gifted from a private collection," explains Gray. "It can work on many levels," she says. "It's as diverse as there are people."

Sarah Murray is a non-fiction author and a writer who has covered the intersection of business, the environment, society and the arts for international publications for more than two decades. She divides her time between the US and the UK.